The Habitability Handbook – an assessment tool for viable island communities

There are about 2,400 small, inhabited, unbridged islands in Europe. Some are far out at sea, while others are situated along the coasts. Some lie in lakes, and some build-up archipelagos. The European islands form a complex, widespread and heterogeneous unit. The total area of our islands is 454,753 km2, with 18,889,077 resident inhabitants. Imagine that all these islands were one nation. This imaginary nation would rank as the 5th European nation in size, between Spain and Sweden. In population, it would be placed after Poland but before Romania.

Each island is unique, but all islands are very different from the mainland. Islands have five particular characteristics:

- Small islands have very dynamic fluctuations in their populations. A small island with 250 all-year residents typically has 2,500 summer residents and 25,000 yearly visitors. The island’s infrastructure – including energy, sewage, ferries, Wi-Fi, healthcare, etc. – serves a couple of hundred persons a day in January but several thousand persons a day in July. The residents of the island, those who “own” the island, are supposed to plan, finance, and implement sustainable solutions for all these challenges – a really wicked problem. Imagine the corresponding numbers for Manhattan (also an island but multi-connected to the mainland); 1.6 million inhabitants on a winter’s day, 16 million or more on a hot day in summer, plus 160 million visitors yearly.

- Small islands are often economically vulnerable. Usually, they are dependent on a small number of economic activities, such as tourism and fishing. A decline in one of them can trigger a major socio-economic shock. This is further worsened by the inevitable competition between residents and tourists for the same limited natural resources, especially for coastal land on the islands.

- As the way to an island goes over water, the journey lasts longer than the equivalent distance on land. For islands, we have to calculate a “perceived distance” rather than the geographical distance. The average speed by car is approximately 70 km/h. If a ferry trip takes an hour to cover ten nautical miles (some 19 kilometres), the perceived distance exceeds the true distance. Waiting times at harbours, rough weather, and ice will make the journey longer, making the island feel more remote, which will affect the habitability.

- In small communities, the number of stakeholders is limited. On the advantageous side, self-governance is easier. The transaction costs are lower as the actors usually know each other and have information on the trustworthiness of other actors. On the contrary, small communities usually have a scarcity of management skills, as many highly educated persons move to urban areas on the mainland with richer work opportunities. Low population numbers also influence anonymity – for good and worse – as conflicts of interest arise easily.

- The governing structure of small islands is often affected by the lack of independence in matters that influence them. Most islands are part of and governed by a bigger municipality. Of all European islands, only two are sovereign states, 32 are regions, states or provinces, and 206 are municipalities. The remaining 2,000 islands are local communities with a local non-governmental and non-municipal organisation, representing the island before relevant authorities in political matters.

What is habitability?

Habitability is the concrete core for assessing the sustainability of an island. Every sustainable society has to be habitable to survive, develop, and keep its resilience. As long as the logistics are efficient and sufficient, an island society has all presumptions to be habitable; there are children in the school, ample workplaces and affordable houses, and islanders feel secure and comfortable.

Naturally, the environment also plays an important role in the habitability process. It is nature that sets the outer limits of our islands, irrespective of where the island is situated; the storms on the Irish Sea, the heat in the Greek archipelago, or the low salinity of the Baltic Sea.

All islanders are experts on their own islands. They live their everyday lives here and know the fluctuations over the year and between the seasons. The question is: Do they know how to make their island more habitable?

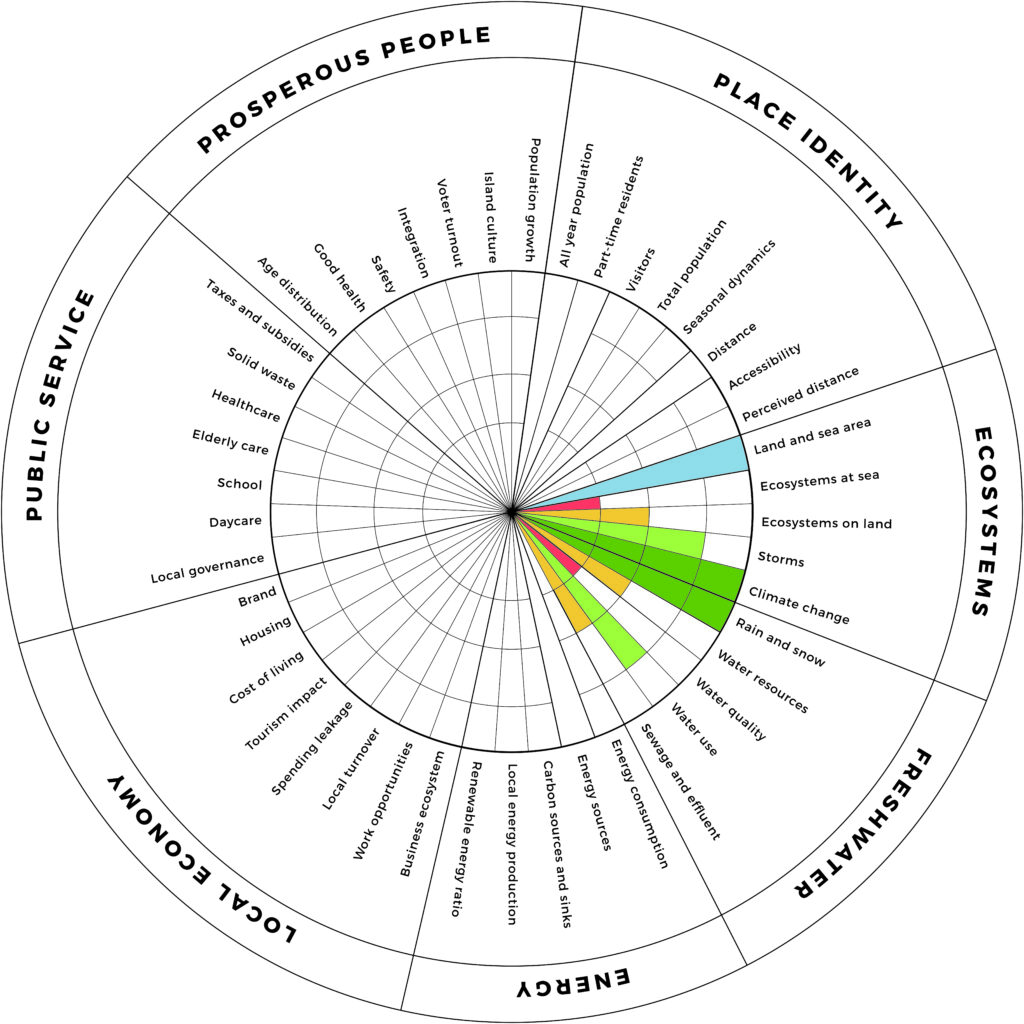

Habitability, in our view, consists of seven aspects. These aspects, or areas, are divided into 45 indicators. The aim is to help you screen your island and focus on the most important parts of your habitability. Which of your strengths will you highlight in your strategies and marketing processes? Which issues need more effort to improve the habitability of your island?

The idea is not to compare islands with each other – an impossible task as islands are quite different – but to help the islands compete with the mainland and show that island living is a good alternative or possibly better.

With the help of the Habitability analysis, it is possible for you to describe and diagnose the habitability of your island, as you and your fellow islanders are its experts. We have intended to create an uncomplicated process but not an unintelligent one. Some indicators are based on facts, like the island’s area, the number of inhabitants, and the number of children in daycare. Other indicators combine regional facts and credible assumptions made by a majority of the islanders, for example, conducted in a survey.

How to use the Habitability Handbook

The Habitability Handbook is primarily designed for the islanders on the more than 2000 small islands in Europe. Our purpose has been to describe the indicators generally enough so that they can be used on an island outside the coast of Scotland and an island in the Baltic or the Mediterranean Sea. Each indicator is rationally described and defined. We present how the result for the indicator is gained; either being an actual number, such as the area of the island, or a calculated value on a four-graded scale. For each indicator, there is a detailed example from a European island.

The seven areas and 45 indicators are based on the habitability analysis from the island of Kökar, Åland, in the Northern Baltic Sea. The original indicators have been revised and sharpened to cover the habitability of any European island better. Nevertheless, we can state that the analysis was developed by islanders, for islanders, to make our islands more habitable. In other words, it is not primarily a tool for scientists but islanders. Much of the information and knowledge will be gathered by citizen science, i.e. the islanders are the experts, and together they will evaluate the state of the habitability on their island.

Talking about islands, we are aware that islands can be very heterogeneous. In some cases, it is easy to define the island and, therefore, its habitability process. An island can be a municipality of its own, including one main island and a reasonable amount of smaller habited islands. This is the case with Kökar. Other cases are more intricate, like islands with very small populations, islands scattered in an archipelago, and islands under heavy stress from depopulation, immigration, war or natural disaster.

This method was developed to suit the needs of small, inhabited, unbridged islands in Europe. It may be of use in other landscapes, in another context – but that was never the intention. If, for example, you would like to perform a habitability analysis on an island with a very small population, you must consider which indicators will be relevant for your analysis. For example, if the island is too small to host a school, but the logistics for the pupils to travel to a neighbouring island or the mainland are functioning, you either have to evaluate the indicator from the reality or explain why you will not assess a certain indicator.

If you live on an island connected to the mainland by one or several bridges, or if you do not live on an island at all, it is still possible to use the Habitability Handbook. However, you must be aware that some indicators may not fit your reality perfectly. In such cases, make a judgement and motivate why some indicators are of no interest.

The seven areas and 45 indicators of habitability

We have integrated the characteristics of small islands described previously into a framework of habitability that consists of seven areas and is measured with 45 indicators.

Printable PDF-version of a blank Sustainability Wheel.

A printable diagram (pdf) of the Areas and Indicators.

The Habitability Handbook describes each indicator in the same manner: (a) its rationale, (b) a definition, (c) how to make the computation, and (d) an example from a European island. Some of the indicators consist of basic facts, such as the area and the population size. Other indicators are numerical on a scale of 1–4, where 1 (red colour) stands for a critical state, 2 (yellow colour) is bad but not in need of immediate action, 3 (light green colour) is good, and 4 (dark green colour) is excellent.

Some indicators are easy to understand and compute, while others are more complex and may demand data from research or a survey. Some ask for a joint judgement from a knowledgeable group of islanders – based on the premise that it is wise to ask kids about kid matters and fishermen about fish.

The Habitability process step by step

To start a habitability process of your island, we recommend the following steps:

- Get to know the tool: the design, purpose and process of habitability. Is it fit for your island?

- Find company. A habitability process is not something you can implement on your own. The process must be led by a core group of practically-oriented enthusiasts between two, at the lowest, and, preferably, four to six persons. The core group will organise the work, set up and keep a realistic timetable, and follow up on the results.

- Invite your fellow islanders. The habitability process must be open, transparent and inclusive. As it is built on citizen science, as many islanders as possible should be involved. Everybody possesses valuable knowledge needed when the information of the different indicators is collected and evaluated: kids, newcomers, businesses, commuters, local politicians and local organisations. In some cases, more in-depth interviews are needed, and in other cases, data is best collected through a survey.

- Make a budget and get financing. You do not have to pay for the method since it was developed with EU financing, but you may need some funds for the project team, especially if you want a project manager to hold the process together. There will be workshops and venues when you must pay for meeting rooms, maybe serve something. You might need a small office, a computer and a telephone. Communication costs money, whether being live or digital. For some indicators, you might want some external or internal experts who are to be compensated. You can get help and advice regarding budgeting and financing from the habitability team at Åbo Akademi and other islands, who have solved this task well.

- Set the goals. What is the purpose of a habitability analysis of your island? For what reason will you use it? Try to be realistic and try not to cover more than you can handle. Describe the red line and arrange an open meeting to agree on the process. It is an important step to get everybody on board and the core group to relate during the journey. Try also to draw a tentative timetable – how long will this first habitability analysis last? The advice is to give it enough time. We are often talking about a year-long process.

- Sort the indicators. Start the habitability analysis by going through all the indicators and making a preliminary judgement if they are relevant to your island. In some cases, there can be some that are not of interest for you to analyse and evaluate. If there are a few, around five or less, they will not have a bigger impact on your result. Of importance is that you all – at least the core group, but in the best case, all islanders invited to a common meeting – agree upon leaving these indicators out. In the result of the analysis, you briefly motivate why this is done. If the majority of the indicators are not relevant or of interest on your island, then you should consider if a habitability process overall is doable for your island.

- Teach your fellow islanders about habitability: what it is, which steps will be taken, how long it takes, how can each and everyone get engaged, what will be asked of them, and what is the final result? This is vital to make everyone confident and included in the process. There are movies and examples on the habitability website, and you can get support from Åbo Akademi University.

- Start the analysis; delegate, inform and keep track. This is the major and most time-consuming step. It is up to you in which order you work with the areas and indicators. In the Habitability Handbook, we have tried to structure the process in a natural way, where we start with the basic facts of the island and the environmental conditions. In reality, they have no mutual order. As a little piece of advice, start with Area 1 – Place identity. The first indicators define your island and are easy to obtain. You will get a quick advance and feel that you are on your way. Another tip is to study the indicators well and make a roadmap on how to advance. Who is doing what? It might be smart to divide the work into several smaller teams. If you are doing interviews and surveys, is it possible to merge information for several indicators into the same questionnaire? In matters concerning potentially new islanders, ask them directly. Try to be as heterogeneous as possible when choosing the respondents for the best overall results. Remember to keep the process transparent. The core group has the responsibility to listen to the islanders, keep everybody involved and informed – open meeting occasions or certain platforms on social media open for everybody interested (or in the best circumstances both) are good ways to perform – and, of course, follow up the process and keep the time table. The core group should also check that all data for all indicators are properly described and that all sources of information are documented. That gives the process dignity and helps to repeat it later.

- Evaluate and document your results. After assessing all seven areas and 45 indicators, you have a complete picture of how habitable your island is. The results of the indicators evaluated in categories 1–4 give a clear and colourful picture of the situation in your habitability wheel. You should now be able to see the strong sides of your island community: which parts of habitability are green? On the other hand, you will certainly see the red ones, your weak points. Are they all – both strengths and weaknesses – expected and known from beforehand, or did you discover any surprises? Make a final report with a summary.

- Celebrate your work. Congratulations, you have done a great job together! Do not forget to celebrate your effort before rushing to further projects.

- Go back to step 4. Now is the time for action, based on the common, open, honest process of clarifying your strengths and weaknesses as a habitable island society.

We wish you Good Luck and enjoy your journey!

How it all started

The habitability process has, until today, only been performed on one single island community: Kökar, one of sixteen municipalities on the Åland Islands, Finland, in the northern Baltic Sea.

The municipality of Kökar was part of an Interreg Central Baltic project, Coast4Us, from 2018 to 2020. The aim was to evaluate the sustainability of the island community. The project engaged a majority of the islanders; 130 of the island’s 232 resident inhabitants actively participated in the work. Besides that, the work involved experts from universities and consultants. However, the project got stuck halfway. Sustainability measurement systems seemed to lack instruments and tools useful on the small-island scale. The characteristics of a small island could not be properly treated, for example, the skewed, seasonal population, the perceived distance, the gross local product or the importance of a diaspora. There was not enough data, or data could not be used as individuals were too easily recognisable.

Instead, the concept of habitability was born. According to the islanders of Kökar, an island society has to be habitable to become sustainable. To be habitable is to be a good choice for living, both for those born on the island and for new residents and families. It calls for a mixed population of all ages, genders, origins and opinions. A habitable and viable island is the most important component of long-term sustainability.

During many meetings, lectures, workshops, municipal committee, and board sessions, the community of Kökar developed forty indicators of habitability. Even though the islanders were involved in the work, the result was partly unexpected. The result led to further plans to make Kökar even more habitable, with the blessing of the municipal board and community council.

The habitability concept of Kökar was also of value to be spread and developed further. Christian Pleijel, who is the inventor of and one of the front persons in the habitability process of Kökar, contacted the Archipelago Institute at Åbo Akademi University in the autumn of 2020 to start cooperation based on the habitability process. The first initiative was an international distance course presenting the concept. The course, which involved over 30 participants from twelve European islands and several island experts – researchers, politicians and mayors – as lecturers, was given in the spring of 2021. The engagement of both students and experts led us to revise and develop the concept further.

During the autumn of 2021, the work for the Habitability Handbook started. Meanwhile, the Archipelago Institute got funding for a project where the concept of habitability is integrated into the development of a national network at the grassroots level for islands and coastal rural areas in Finland. A team consisting of Christian Pleijel, Pia Prost and Cecilia Lundberg – with the help of many islanders and island experts around Europe – have now further developed the concept to its present form.

The Habitability Handbook – An assessment tool for viable island communities by the Archipelago Institute at Åbo Akademi University is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.