The finite borders of an island create unique ecosystems – as described in biology, ecology, earth science, meteorology, and geography. It also creates a singular business ecosystem: a local economic context with arrangements brought forward by the smallness of the territory, the limited resident population, the scarcity of resources (raw materials, infrastructure, human potential), as well as the isolation caused by the sea.

There are economic advantages of insularity, such as low competition and tourist success, but also many disadvantages that oblige the island economies to set up a particular management system.

We will define the local economy of an island as a business ecosystem by examining the local turnover, how much money is leaking out of the island, the impact of tourism, work opportunities, if there is affordable housing, how expensive it is to live on the island, and how strong the brand of the island is – as a place to inhabit.

Indicators in the Local economy area:

- (24) Business ecosystem

- (25) Work opportunities

- (26) Local turnover

- (27) Spending leakage

- (28) Tourism impact

- (29) Cost of living

- (30) Housing

- (31) Brand

Indicator 24: Business ecosystem

Business economics is usually focused on value chains, meaning how the price of a product or service is gradually built until it is finished and sold to a customer. Someone grows fodder for someone who has chicken and hatches eggs that are sold to a store that sells them to their customers. The purpose of describing value chains is to set the right prices to maximise profits and minimise costs.

On islands, we’d like to focus on business ecosystems instead: the entire network of customers, employees, suppliers, subcontractors, competitors, distributors, investors, infrastructure, and authorities involved in creating an island product or island service through less competition and more collaboration. All parts of a business ecosystem affect and are affected by the others, which creates a dynamic relationship – as in a biological ecosystem, where everyone is dependent on everyone.

The theory emerged from the rapid technological changes of recent decades, globalisation, and periods of financial turbulence. It was presented by Professor James Moore in 1993. Moore claimed that companies must be developed together, across company boundaries. He said that success increasingly requires cooperation between many stakeholders, many actors, both private and public.

Although the theory was first tested in Silicon Valley to describe how Apple grew, it also fits well on an island; this is the way many small Irish and Scottish islands are organised. To reduce costs, their food producers placed joint orders for feed. It provided economies of scale, and the unit cost for the individual farmer was lower than if they had each made their own small, individual purchases. Together, they improved their marketing and collectively bought expensive equipment that the individual farmers could not otherwise afford.

Sometimes island cooperatives for special products were developed, but most often cooperatives with a broad focus and a general, multifunctional business such as Comharchumman Inis Meain Teo – on Inishmaan, one of the Aran Islands – with an annual turnover of thousands of pounds. This cooperative has renewed the electricity system, renovated the town hall, and built and now manages the system for water distribution with tanks, pumps, filters, pipes and metres. Additionally, they run a summer school in Gaelic, have built a football field, the island’s telephone network and telephone exchange, paved the runway for flights, and own and manage a textile factory.

Typically, business ecosystems comprise six main areas. Some of these areas can be partially defined using other resilience indicators.

| Area | Ecosystem activities on islands | Related indicators |

| a Marketing | A smart and well-groomed common brand that has support and funding from all parties | Perceived distance (8) Brand (31) |

| A well-maintained common customer database, accessible to all | ||

| b Work opportunities | Joint efforts to recruit and retain skilled labour on the island | Living costs (29) Affordable housing (30) Daily care (33) School (34) Subsidies & tax (38) Integration (42) |

| c Suppliers | Support for local suppliers regardless of higher prices | Accessibility (7) |

| Joint acquisitions from the mainland | ||

| d Infrastructure | The island’s companies have a strong collective representation in the bodies on the mainland that are responsible for hard and soft infrastructure | All indicators related to water, energy and municipal services |

| e Support from authorities | Local authorities are knowledgeable about, aware of and provide active support to the island’s business community | Local Governance (32) |

| f Investors | Joint efforts to obtain appropriate regional, state and EU support | |

| Successful contacts with the island’s diaspora* |

*Diaspora is a term for former islanders and their descendants who no longer live on the island but have a strong love for it. The word is taken from the Bible, where it is used to reference Jewish people in Babylonian captivity. Ireland, for example, has a very large diaspora with many millions of emigrated Irish. Small islands with large emigration, such as Kastellorizo in Greece and Susak in Croatia, have a diaspora with a huge impact on island life and industry through investment, trade, tourism, and philanthropy.

b Definition

The extent to which joint efforts to reach customers and labour, keep costs down, reach suppliers, ensure proper infrastructure, obtain public support, and obtain capital constitutes a strong, cooperative business ecosystem on the island.

c Computation

Level of collaborations between companies, organisations, authorities and investors

| Level of collaborations between companies, organisations, authorities and investors | 1

Non-existent |

2

Low |

3

Ok |

4

High |

| a | Island brand | |||

| Customer database | ||||

| b | Joint efforts to recruit labour | |||

| c | Local suppliers | |||

| Joint acquisitions | ||||

| d | Ensuring the right infrastructure | |||

| e | Support from authorities | |||

| f | Financing | |||

| Well managed diaspora | ||||

| Sum = (a+a+b+c+c+d+e+f+f)/9 | ||||

d Example

Ærø is a large 88 km² island located in the southern inlet to the Little Belt, said to be the most beautiful island in Denmark. One of the smallest municipalities in the country, with 5,951 islanders in 2021. The main town Ærøskøbing is well preserved with mediaeval origins, colourful houses, original exterior doors, and cobbled streets.

The island has more than 20 daily ferry trips. There is virtually no traffic, the buses are free, and crime is as close to zero as possible on our planet. It is a wonderful place to stay and to visit.

A large part of Ærøs economy is based on tourism. The island is a popular place for getting married. Weddings of foreigners on Ærø rose from a few hundred in 2008 to 5,338 in 2018. It was partly down to Danish bureaucracy – or lack of it – and the country’s open and tolerant nature to same-sex weddings. The average European couple who got married within the last five years spent a median of 5,000 euros on their wedding or civil partnership. The wedding industry brings millions of euros to Ærø.

This wedding industry has evolved into a strong business ecosystem made up of the local food industry, restaurants and hotels, the church, shops, service companies, and transportation, including horse carriages and Ærø’s own airline Starling Air. Also adding to its brand, Ærø has a remarkably high share of renewables in electricity, with wind energy as an important source. Ærø EnergyLab manages energy-related projects for the municipality of Ærø and welcomes visitors from around the world to explore the island’s energy solutions. In 2021, Ærø was awarded the RESponsible Island Prize 2020 by the EU Commission.

| Island brand | 4 |

| Customer database | 3 |

| Joint efforts to recruit labour | 3 |

| Local suppliers | 4 |

| Joint acquisitions | Unknown |

| Ensuring the right infrastructure | 4 |

| Support from authorities | 4 |

| Financing | 4 |

| Well managed diaspora | 3 |

| Summa 4 + 3 + 3 + 4 + 4 + 4+ 4 + 3) / 8 | 3,6 |

Ærø scores a 4.

Addition

Natural ecosystems are affected and threatened by macro-level changes such as global warming and invasive species. The same applies to business ecosystems: in 2019, the Danish law prohibited pro forma marriage and made it much more difficult for foreigners to marry in Denmark.

Due to this and also covid-19, the number of marriages on Ærø fell to 2,502 in 2020 and 2,400 in 2021. In the coming years, we will see if Ærø’s creative and cooperative cooperation model will be able to adapt its ecosystem to new conditions.

References

- Anon. 28 August 2021. 2,400 bliver gift på Ærø i 2021. Ærø Dagblad.

- Adnar, R, Oxey, J & Silverman, B. 2013. Collaboration and Competition in Business Ecosystems. University of Toronto.

- Danish Islands Weddings. https://www.danishislandweddings.com

- van Dijk, M, Mecozzi, V, Kemp, L & Laline, R. Ecosystems and value chains. THNK – School of Creative Leadership.

- Grydehöj, A. 2011. Negotiating heritage and tradition: identity and cultural tourism in Ærø, Denmark. Journal of Heritage Tourism.

- Stephan A Royle. 2001. Island co-operatives in: A Geography of Islands.

Indicator 25: Work Opportunities

a Rationale

If an island is to be habitable, there needs to be available work. It might be working at a commuting distance or work that can be done distantly, at least partly. A prerequisite for remote work is good technical solutions on the island, for example, a well-functioning network connection. Many prefer to work on the island to avoid commuting or working as a sailor away from home for long periods (quite common on islands). If a couple or a family wants to be able to stay or move in, there must be work opportunities for two people. If there are different types of workplaces in several sectors, the chance of finding suitable work increases.

b Definition

The number of jobs on the island in relation to how large the labour force is (workplace supply), unemployment rate, the proportion of islanders working on the island, and how widespread the industry is on the island.

c Computation

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Low | Acceptable | Good | Very good | |

| Workplace supply | Less than 50% | 50-69% | 70-89% | Over 90% |

| Network connection | Absent or limited | Unstable | Well-working | Broadband or high-speed connection |

| Unemployment rate | More than 10% | 7-9% | 4-6% | Less than 4% |

| Proportion of islanders working on the island | Less than 40% | 41-60% | 61-80% | More than 80% |

| Industry spread | Workplaces are mainly in one sector | Workplaces are mainly in a couple of sectors | Workplaces are relatively well spread across several different sectors | Workplaces are well spread across several different sectors |

It can be difficult to find official data on a small island, which means field studies are needed. Be careful not to single out individuals or groups when the number of inhabitants is low.

d Example

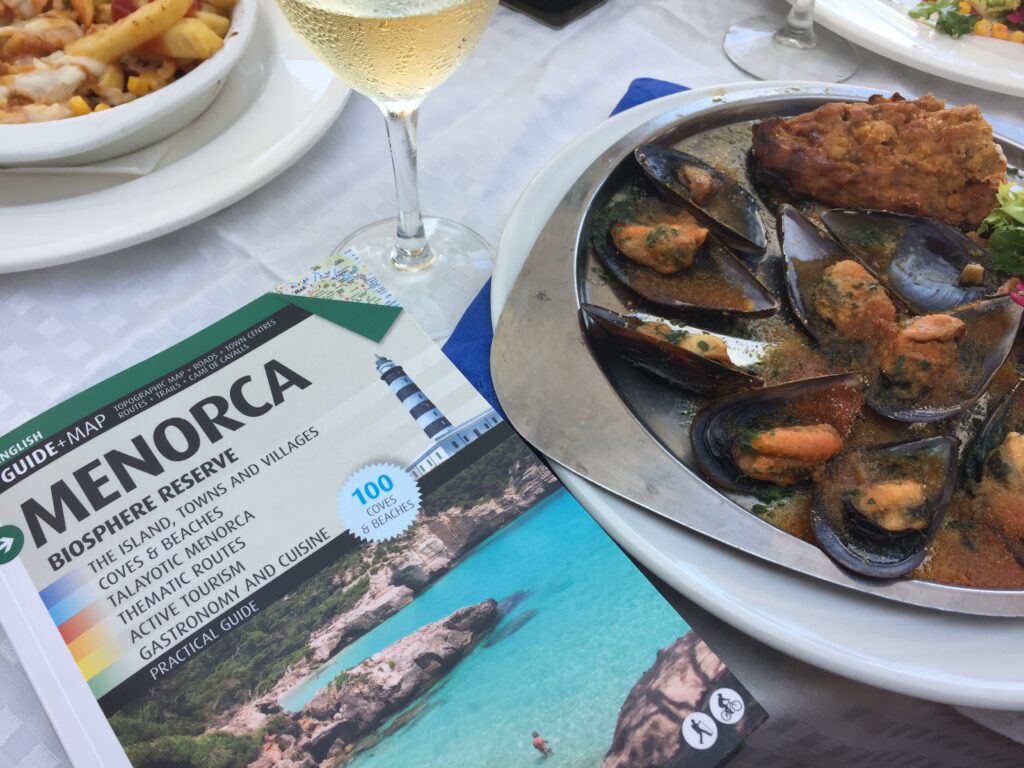

Menorca is an island located northeast of Mallorca, 53rd in size among Europe’s islands, with a land area of 660 km2 and a resident population of 99,037 (in 2021). The island is Mallorca’s little sister, with a fifth of its area, a tenth of its population and a fourteenth of its tourists. The number of tourists was about 1 million in 2021.

The dairy industry is significant; 30,000 motley cows graze on the island. At the end of the 19th century, almost 40% of the population subsisted on shoe manufacturing. “Abarcas”, leather sandals with soles made of car tires, are typical for Menorca. The most famous shoe factories are in Alaior and Ferreries. Also, various fashion accessories are made of leather: bags, vests, belts and jackets.

There are about 47,000 permanent jobs in Menorca. The population is almost doubling during the high season due to the amount of labour-active in various hospitality industries, so labour supply is very good.

| Sector | Number of jobs | Percent of BLP |

| Agriculture and forestry, fishing | 550 | 0.5 |

| Manufacturing | 3,100 | 7.5 |

| Construction | 4,000 | 6 |

| Services: | 86 | |

| Accommodation, food, trade, local transport | 19,200 | 36 |

| Real estate | 500 | 17 |

| Public administration | 9.100 | 16 |

| Industry (except construction) | 7.5 | |

| Qualified services | 4.600 | 7 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 4.700 | 5 |

| Finance and insurance | 960 | 3 |

| Information & communication | 2.5 |

Employees in accommodation, food, trade, and local transport make up 40% of the permanent workforce and provide 36% of BLP.

The proportion of the workforce working on the island is nearly 100%. When the demand for labour increases in the high season, the number of employees also increases, especially in unskilled occupations–all without BLP increasing. Jobs with low-skill requirements, such as waiters, cleaning staff, kitchen assistants, or bricklayers, are prone to low salaries and generally poor conditions.

There is a 14% risk of poverty in Menorca.

| Most common occupations | No of employees |

| Waiters and bartenders | 4.900 |

| Cleaners | 2.700 |

| Sales | 2.000 |

| Kitchen aids | 1.100 |

| Masons | 1.000 |

| Chefs | 970 |

| Bricklayers | 700 |

| Administrators | 580 |

| Housework | 560 |

| Composers, musicians and singers | 540 |

Unemployment was 10.6% after the island recovered from the Covid-19 restrictions, but still 21.4% among young people under 25 years.

Most companies are small: 3,500 companies have no workers other than the owner, 2,000 companies have 1-2 employees, 660 companies have 3-5 employees, 250 companies have 6-9 employees, 70 companies have 10-19 employees, and 40 companies have more than 20 employees. It does not entice families to move to Menorca. There is a Balearic Islands Employment Plan to address the labour market shortcomings.

| Type | No of employees | Turnover | No of companies |

| Micro | Fewer than 10 | 2 MEUR | 96% |

| Small | Fewer than 50 | 10 MEUR | 3% |

| Medium | Fewer than 250 | 50 MEUR | 0,4% |

| Large | More than 250 | Exceeds 50 MEUR | 0,1% |

The industry spread is relatively small, with a focus on tourism and real estate. Real estate investments account for more than 80% of all foreign investments. In 2015, EUR 261 million was invested in Menorca, mainly through the purchase and sale of hotels. The majority (143 million) were German capital, closely followed by Great Britain.

Menorca gets a mixed rating:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Workplace supply | 4 | |||

| Unemployment rate | 1 | |||

| Proportion of the workforce working on the island | 4 | |||

| Industry spread | 2 |

Sum (4 + 1 + 4 + 2) / 4 = 2,75.

The indicator value for Menorca is 3.

References

- Alcaraz, F. C. 2018. Active Labour Market Policies in Economies Based on Tourism: the Balearic islands Experience. Cuadernos de Turismo, nº 41, (2018); pp. 75-106 (PDF).

- countryeconomy.com: Balearic Islands, unemployment rate.

- Francisco Caparros Alcaraz, University of Madrid: Active Labour Market Policies in Economies Based on Tourism: the Balearic islands Experience (2018) (PDF).

- Llurdes, J C & Torres-Bagur, M. 2019. Menorca: From the third tourism boom to the economic crisis and the role of the Insular Territorial Plan. 9. 39-67. 10.2436/20.3000.02.47.

- Pla d’Ocupació de Qualitat 2017-2020.

- Second Homes — True pillar of Menorca’s economy?

Indicator 26: Local turnover

a Rationale

A part of the local economic analysis is monetary, with money used as a measure. In a country, a nation, the value of all goods and services produced in one year is its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This measure provides an economic snapshot of the size of the country’s economy and growth. GDP can be calculated in three ways: using expenditure, production and/or income.

Ever since local economic thinking and analysis were introduced twenty years ago, it has been challenging to measure a gross local product – what villages, towns, rural areas, or islands are worth in monetary terms. Three good attempts have been made by the Swedish islands Ven in the Sound (in 2013), Holmön off Umeå (in 2020) and Nämdö in the Stockholm archipelago (in 2021). They have based their calculations on the turnover of local companies and the taxable income of the inhabitants.

Holmön outside Umeå went a step further because they had difficulties obtaining data from Statistics Sweden, which does not release data on places with less than 200 inhabitants – Holmön has about 70 registered inhabitants. The people of Holmön were creative; based on local knowledge, they produced figures about their island. They also decided that everyone who stays on Holmön should be included in the statistics because everyone contributes to creating a basis for the available services.

On Nämdö in the Stockholm archipelago, with the support of researchers Cecilia Solér and Robin Bankel from the Department of Business Administration at the University of Gothenburg, it was calculated:

how much money the companies in the archipelago turnover:

- how large the total taxable income of the inhabitants is;

- how much money is spent by the island residents in the archipelago and how much is spent on the mainland.

- how much of the work carried out by companies in the archipelago takes place in the archipelago or other places.

This knowledge has since been used to understand what may need to be done to strengthen the local economy in various ways.

b Definition

The gross local product consists of (i) the companies’ total turnover and (ii) the inhabitants’ total taxable income.

c Computation

(i) The companies’ total turnover is obtained from the National Tax Agency

| Number of Companies | Total turnover |

(ii) The total purchasing power of the inhabitants can be calculated with the expenditure method – how much the individuals spend, or with the income method – all persons over 20 years of age with a taxable income.

The expenditure method

Average household costs can be obtained from national statistical databases, sometimes broken down into urban and rural areas.

| Average per household | Total for all the island’s households | |

| Food | ||

| Non-alcoholic beverages | ||

| Restaurant meals | ||

| Alcoholic beverages | ||

| Tobacco | ||

| Consumables | ||

| Household services | ||

| Clothes and shoes | ||

| Residence | ||

| Furniture | ||

| Healthcare | ||

| Transportation | ||

| Leisure and culture | ||

| Sum |

The income method

The number of inhabitants multiplied by their average income before tax.

| Total income | |

| Taxes | |

| Left in purchasing power |

d Example

Ven is situated in the middle of the Öresund strait, two nautical miles from Sweden and four nautical miles from Denmark. Maritime traffic past Ven is intense, with about 75,000 ship movements per year (200 a day). The island has an area of 7.5 km².

There are 370 residents on Ven; 160 people registered elsewhere live permanently on the island, and there are 30 part-time residents and 60 summer residents. Ven has 130,000 yearly visitors, mainly day-trippers who spend a day biking around the small island during the summer months. Some visitors stay overnight.

Ven was a Danish island until 1660, when Denmark and Sweden swapped Bornholm and Ven. Eventually, the island became a municipality of its own. In 1959, it was integrated into the mainland city of Landskrona. The islanders of Ven have always felt they are something the cat dragged into Landskrona, which has no other island. The 370 residents of Ven constitute less than 1% of Landskrona’s population and 3% of its area. For people on Ven, it is important to clarify whether they bring a surplus or a deficit to their land-based municipality. It is important to clarify not only for the reasons of self-esteem and pride, but also to understand how to develop the local economy, make the island more habitable, and bring new residents to Ven.

The companies’ total turnover

In 2013, there were over 70 companies at Ven and 160 professionals, which equals one company for every other professional, mainly small companies. One company had 20 full-time employees. One-third of the companies were service companies in the tourism industry. The rest were mixed with a small number of food processors (distillery, dairy, mill, oil press, bakery, pasta production, jams and marmalades).

| Number of Companies | Total turnover |

| 70 | 48,5 million SEK |

In addition, the project was able to map where the companies’ revenues came from:

| All-year residents | 5 milj SEK |

| Part-time residents | 7 milj SEK |

| Visitors | 36,5 milj SEK |

Residents’ expenditure

With the help of The Swedish Bureau of Statistics, the estimated average costs for households in sparsely populated areas and surveys that show how much money Ven residents spend on the island and the mainland, the following figures could be calculated:

| Average according to statistics | Total 120 households | On Ven | Outside Ven | |

| Food | 38.240 | 4,588.000 | 2.154.000 | 2.434.800 |

| Non-alcoholic beverages | 3.050 | 366.000 | 172.000 | 194.000 |

| Restaurant meals | 8.210 | 985.200 | 500.000 | 485.200 |

| Alcoholic beverages | 3.970 | 476.400 | 476.400 | |

| Tobacco | 2.320 | 278.400 | 130.000 | 148.400 |

| Consumables | 6.570 | 788.400 | 370.000 | 418.400 |

| Household services | 15.140 | 1.816.800 | 100.000 | 1.716.800 |

| Clothes and shoes | 12.460 | 1.495.000 | 1.495.200 | |

| Residence | 74.560 | 8.947.200 | 1.200.000 | 7.747.200 |

| Furniture | 20.630 | 2.476.000 | 2.475.600 | |

| Healthcare | 7.600 | 912.000 | 90.000 | 822.000 |

| Transportation | 60.090 | 7.210.800 | 200.000 | |

| Leisure and culture | 56.790 | 6.814.000 | 120.000 | |

| Sum SEK | 309.630 | 37.155.600 | 5.036.000 | 32.119.600 |

Residents’ income

In 2011, 298 residents had an average income before taxes of 232.771 SEK.

| Sum of income | 69.365.886 |

| 20,24% municipal tax | – 14.039.655 |

| 10,39 county tax | – 7.207.116 |

| Left in purchasing power | 48.562.080 |

Per household (120 st)

| Purchasing power | 404.684 |

| Spent on Ven | 42.000 |

| Spent on the mainland | 268.000 |

| Savings (for example amortisation) | 95.000 |

Addition

Ven has calculated its resident population with a taxable income: 298 people. If they had done as Holmön and Nämdö – which we advocate – they should have included their 160 permanent dwellers (residents of Landskrona but living all year on Ven), 30 part-time residents and 60 summer residents.

| Category | Number of persons | Number of days | Number of days on the island |

| All-year residents | 298 | 365 | 108,770 |

| Permanent dwelling | 160 | 365 | 58,400 |

| Part-time residents | 30 | 120 | 3,600 |

| Summer residents | 60 | 45 | 2,700 |

| Sum | 173,470 |

173,470 days of stay correspond to an average population of 475 people. The total income will then be SEK 110 million, taxes to Landskrona, 22 million, and to the region, 11 million. One purpose was to show Ven’s monetary value for the mainland.

| Sum of income | 110.566.225 |

| 20,24% municipal tax | – 22.378.603 |

| 10,39 county tax | – 11.487.116 |

| Left in purchasing power | 76.700.506 |

References

- Lokalekonomisk analys Holmön (PDF).

- Statistikdatabasen, 1999–2001. Utgifter för hushåll (HBS) efter H-region och utgiftsslag (COICOP).

- Økonomi – grunden för vår existens. Hvens lokala ö ekonomi (PDF).

Indicator 27: Spending leakage

a Rationale

Spending leakage is the act of money leaving the island and ending up elsewhere. With the world becoming increasingly globalised and monopolised by the most successful multinational corporations, economic leakage is becoming more and more prevalent. Highly specialised economies, such as isolated mining towns or small islands that are less able to meet the needs of the local households, will find that consumers are making periodic non-local shopping trips or doing a lot of online shopping.

Keeping more money on the island is one of the best ways of strengthening the whole island economy.

b Definition

How much of the islanders’ available income is spent on the island.

c Computation

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Less than 10% | 10-25% | 26-49% | Over 50% |

d Example

Returning to Ven (indicator 26), figures in euro according to Statistics Sweden (SCB):

| Per household |

120 households |

Expenses made on Ven |

Expenses made on the mainland |

|

| Provisions | 3,511 | 401,097 | 197,784 | 223,567 |

| Non-alcoholic beverages | 280 | 31,987 | 15,793 | 17,813 |

| Dining out | 753 | 86,023 | 45,911 | 44,552 |

| Alcoholic beverages | 365 | 41,698 | – | 43,744 |

| Tobacco | 213 | 24,333 | 11,937 | 13,626 |

| Consumables | 603 | 68,887 | 33,974 | 34,418 |

| Household services | 1,390 | 158,794 | 9,182 | 157,639 |

| Clothes and shoes | 1,144 | 130,691 | – | 137,291 |

| Residence | 8,646 | 987,719 | 110,186 | 711,360 |

| Furniture and fittings | 1,894 | 216,371 | – | 227,313 |

| Healthcare | 698 | 79,740 | 8.264 | 75,477 |

| Leisure and culture | 5,518 | 630,376 | 18.364 | 643,743 |

| Transportation | 5,215 | 595,762 | 11.019 | 614,727 |

| Sum | 28,431 € | 3,247,957 € | 462,413 € | 2,949,272 € |

The people of Ven pay almost half a million euro for goods and services on the island, but 3 million on the mainland. Out of a ten euro bill, 90 cents is spent in the local grocery shop and local restaurants, 45 cents on local services, and the remaining 8,65 are used for buying groceries, paying the rent, gasoline, bus and ferry tickets, sport and cultural activities which all is paid on the mainland.

Looking at an individual level, the spending leakage is quite huge:

| Per resident | 16,000 € |

| Per household | 39,000 € |

| Of which is consumed on the island | 3,500 € |

| Of which is consumed on the mainland | 27,000 € |

| Savings | 8,500 € |

Out of a total of 3,247,957€, only 14% (462,413€), was spent on Ven. Therefore, the value for Ven is 2.

References

- Eurostat. Household expenditure by category, European Union, 2020.

- Statistikcentralen. Över hälften av utgifterna hos låginkomsttagarna går till boende och kost (Statistics on household expenditure in Finland).

- Statistikmyndigheten. Hushållens utgifter (HUT) (Statistics on household expenditure in Sweden).

- Statistikmyndigheten. Genomsnittliga utgifter i kronor per hushåll, 2003–2012 (Fasta priser) (Median household expenditure per category in SEK).

Indicator 28: Tourism Impact

a Rationale

Tourism is a predominant sector on many (most) small islands. It differs from other industries, such as agriculture, fishing, shipping and trade, in that 60-90 percent of the money a customer (tourist) spends during a stay leaks back to airlines, hotels and travel companies, mainly in the tourist’s home country. Calculating the importance of tourism is important to understand how dependent the island community is on this industry, which does not bring as much revenue as it might seem.

b Definition

Percentage of local turnover emanating from tourism.

c Computation

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Over 80% | 60-80% | 40-60% | Under 40% |

D Example

The Isles of Scilly is an archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall. The islands have a separate local authority: the Council of the Isles of Scilly.

The islands have successfully attracted visitors due to their special environment, favourable summer climate, relaxed culture, efficient coordination of tourism providers, and good transport links by sea and air to the mainland, uncommon in scale to similar-sized island communities. Tourism on Scilly is a highly seasonal industry owing to its reliance on outdoor recreation and fewer tourists in winter, resulting in a significant constriction of the islands’ commercial activities.

The number of tourists who make the 45-kilometre journey by boat, plane, or helicopter each year is about 125,000. There are also some 40 cruise ships with 17,500 passengers coming ashore to see what the islands offer. Tourism employs 70% of the island’s 2,224 (2019) permanent inhabitants.

Tourism shapes the pattern of life on the islands by sustaining employment and the population level. It also generates income and business rates and sustains the transport links that would otherwise be fewer and of doubtful viability. It supports the school’s viability and hence opportunities for families and young people to stay on Scilly. Tourism generally supports the essentials of an existence with modern comforts – shops, restaurants, health services, building trades. It provides a job (sometimes 2 or 3) for more or less anyone who wants one, which means unemployment is low.

Under a more critical view, tourism has locked Scilly into a seasonal economy with under-employment during the off-season and income levels below the national average. Transport and services of all kinds are scaled to cope with the peak demand and are oversized and difficult to maintain at other times. The visitor influx puts a significant demand on already ageing infrastructure for power, water, and waste disposal. Self-catering accommodation, second homes, and staff accommodation take up many of the available beds, causing high prices and a housing shortage. The specialisation in tourism creates risks in a downturn and has perhaps blocked diversification into other sectors.

While wildness and remoteness attract many visitors, they also demand almost everything to be shipped in, driving up the costs of living and doing business and chipping away at the competitiveness of the islands. Construction and improvement of buildings are particularly expensive and add further caution to investment decisions.

There was a decline in arrivals by the main transport modes from 2005 to 2010 – from 111,420 to 102,381. With Scilly’s economy so dependent on tourism, the decline in visitors threatened its whole structure.

The Islands’ Partnership, which is responsible for marketing Scilly as a destination, had projected that 70,000 visitors would spend £34m on the islands during 2020. However, Scilly was closed for tourists from March 21 as all flights and passenger ferry services were suspended. The COVID crisis and the lockdown could not have happened at a worse time for the tourism and hospitality sector: at the end of the winter, when cash flow is traditionally at its lowest and borrowing at its highest. Since then, tourism has not generated income whilst covering fixed costs and paying back booking and deposits.

Pre-Covid, tourism was estimated to account for 85% of the islands’ income, bringing some £50million to the Scilly Islands’ economy each year.

In February 2022, the Council of Scilly adopted a Corporate Plan with four areas: (1) Housing, (2) Climate change and waste management, (3) Transport and highways, (4) Community wellbeing and fairness. Now the question is not how the islands will recreate their former tourism, but “how do we bring tourism back better?”.

The value of Scilly is 1.

References

Indicator 29: Cost of living

a Rationale

Islands have a limited local market and transport time/costs, leading to a higher cost of living compared to the mainland.

b Definition

Comparison of costs on 25 everyday articles and other goods.

| Necessity | Price on the island | Price on the mainland |

Comparison (percentage) |

| Shopping cart | |||

| Potatoes | |||

| Coffee | |||

| Milk | |||

| Oats | |||

| Sausage | |||

| Fish (salmon) | |||

| Apples | |||

| Bread | |||

| Cheese | |||

| Sum | |||

| Other goods | |||

| Petrol | |||

| Pizza (nice restaurant) | |||

| Rent/m2 | |||

| Gravel 1 m3 | |||

| Room for 2 in a hotel | |||

| Average | |||

c Computation

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| More than 25% more expensive than on the mainland | 10 to 20% more expensive | Less than 10% more expensive |

Cheaper than on the mainland |

d Example

Kökar (population 232) is situated 31 nautical miles plus 30 kilometres from Mariehamn (population 15,000), the capital of the Åland Islands. The grocery shop on Kökar gets deliveries by lorry and ferry. The customer base on Kökar is small, and, in the end, the customers pay the extra costs for the long deliveries (in nm, km and time).

This is the price comparison from 2018 between a large grocery shop in Mariehamn and the small grocery shop on Kökar, euro per kilo:

| Necessity | Price on Kökar | Price in Mariehamn | Kökar / Mariehamn percentage |

| Shopping cart | |||

| Potatoes | 1.29 | 0.94 | 137 |

| Coffee | 9.98 | 3.89 | 256 |

| Milk | 1.30 | 1.27 | 102 |

| Oats | 2.71 | 1.09 | 249 |

| Sausage | 5.73 | 5.48 | 105 |

| Fish (salmon) | 22.90 | 17.90 | 128 |

| Apples | 2.69 | 2.99 | 90 |

| Bread | 4.53 | 3.70 | 122 |

| Cheese | 13.90 | 4.69 | 296 |

| Sum | 148 | ||

| Other goods | |||

| Petrol | 1.60 | 1.37 | 117 |

| Pizza (nice restaurant) | 13.50 | 13.50 | 100 |

| Rent/m2 | 7.50 | 9.50 | 78 |

| Gravel 1 m3 | 35 | 10 | 350 |

| Room for 2 in a hotel | 152 | 135 | 113 |

| Average | 151 | ||

Kökar gets the value 1 since the island is more than 25% more expensive than the mainland.

Indicator 30: Housing

a Rationale

“Small island communities are experiencing a peculiar paradox: the number of permanent residents is decreasing, but there is still a shortage of housing for new and returning islanders”, ESIN wrote in its report “Meeting the Challenges of Small Islands” in 2007. The demand for vacation homes and second homes creates inflation on the island property market.

b Definition

Price level on property.

c Computation

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Very high | High | Moderate | Low |

d Example

Denmark has 27 small islands that are not municipalities and therefore lack a vote in the Danish parliament. In 2015, Professor Jørgen Møller from Aalborg University proposed shutting them all down. The reason for this was that one in seven inhabitants had left these islands since 2003, and that the 4,605 inhabitants cost the state 14 million euros per year – mainly in ferries. “It can be boring too, can’t it?” said Jørgen Møller in a radio interview, meaning island life in general, which he apparently did not really understand.

The statement received a lot of attention in the Danish media. Dorthe Winther, a resident of Omø, commented: “There is an old saying: Bad publicity is better than no publicity. In this case, one is tempted to say that bad publicity is even better than good publicity. What started as a negative story about the small islands has caused the islanders to fight, the media to clear the square – and most importantly: It has made people listen. Listen to the story of what kind of life the small islands offer. Thank you, Jørgen Møller, you have put the spotlight on the small islands, and we are glad for that.”

Omø is a small island in the Great Belt with 166 permanent residents who make a living from fishing and agriculture. It belongs to Slagelse municipality, where the houses cost DKK 16,120/m2. On a list showing which of Denmark’s 98 municipalities are the most expensive to buy a house in, Slagelse came in at number 52. Samsø, Laesø, Aerø (indicator 24) and Langeland all end up far down the list. There are no statistics for Omø (it is not a municipality), but there are two houses for sale in late summer 2022: the old bank and bakery for DKK 2,750/m2 and a house with a view of Kirkehavn for DKK 11,824/m2. However, nothing is available for rent.

In 2020, the Danish government decided to allocate DKK 30 million to subsidize the construction of public housing on small Danish islands and the island municipalities of Fanø, Laesø, Samsø and Aerø during the period 2021-2026. DKK 404,000 can be granted per house construction. The municipal council must apply, but the developer gets the money. DKK 20,020 can be granted in annual rent reduction for existing homes.

Apparently, the government does not have the same solution to the housing issue as the professor who wants to buy out the islanders so that their houses can be used as holiday homes, writers’ cottages and summer camps.

Dorthe Winther can be proud. She came to Omø with her husband, both teachers, in 1988. In 2001 she was elected chairman of the Association of Danish Small Islands, which represents 27 islands that are not municipalities. She is most satisfied with the “Landevejsprincippet”, which states that it should cost the same to travel a distance by ferry as the corresponding distance by road. After 22 years, she quits as chairman 2022, and can also be satisfied with how the government’s housing agreement also covers the small islands in Denmark. Will the rental subsidy stimulate the local rental market in Omø?

Indicator 31: Brand

a Rationale

There are two sides of a brand: identity and image. Identity signifies what we have and who we are, image who we want to be. Our image is created by how others see us – think about how our personal image among friends and family may differ from our image at work.

Islands with a strong image are prison islands like Gorgona in Italy and Bastøy in Norway. Poveglia in Venice’s lagoon, said to be the most haunted location in Italy, combines a terrible image with a strange identity, attractive for some. The island of Mont Saint-Michel in France is an iconic image which attracts 2.5 million visitors every year (pre-Covid), but it has only 44 residents.

Speaking of habitability, our aim is to attract immigrants. Not mere visibility or visitability. In this context, we don’t want people to tour our island, we want them to stay – regardless if they were born here or elsewhere. We want them to root themselves here. Not tourism, but rootism.

b Definition

How well-known your island is among people you want to attract.

c Computation

The strongest tool for measuring the island brand is probably a survey directed at people outside the island, belonging to the segments you want to attract, supported by a survey directed at people who have recently moved to the island, or left it.

Establishing your image as an island is primarily a sales and marketing challenge. To calculate the indicator value of your island, there are a number of possible indicators which should be used together:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Weak brand | Medium brand | Strong brand, unique image, but not with a focus living |

Strong brand, well-known as a good place for people to live | |

| Printed media last year | No articles | A few articles, mostly touristic | Many articles, some describing the island as a good place to live | Active contacts with media to get the island well known to possible new islanders |

| Hits on the internet | Under a million | 1-3 millions | 3-9 millions | Over 10 millions |

| Population growth | Negative | Stable | Positive (over 5% the last 10 years | Very positive (over 10% last 10 years) |

| Published research | Not known | A few works published but not known to or used by the island community | A few works published which are communicated to the island community |

Close contact with a university, students and researchers are welcome and actively studying different aspects of island life |

| Active diaspora | Not activated | Irregular activities, mainly activated by the diaspora | Frequent activity, some regular support | Strong support, many activities, “Ambassador” program |

| Survey | Not done | Planned | Done but outdated | Recent, well-made survey |

d Example

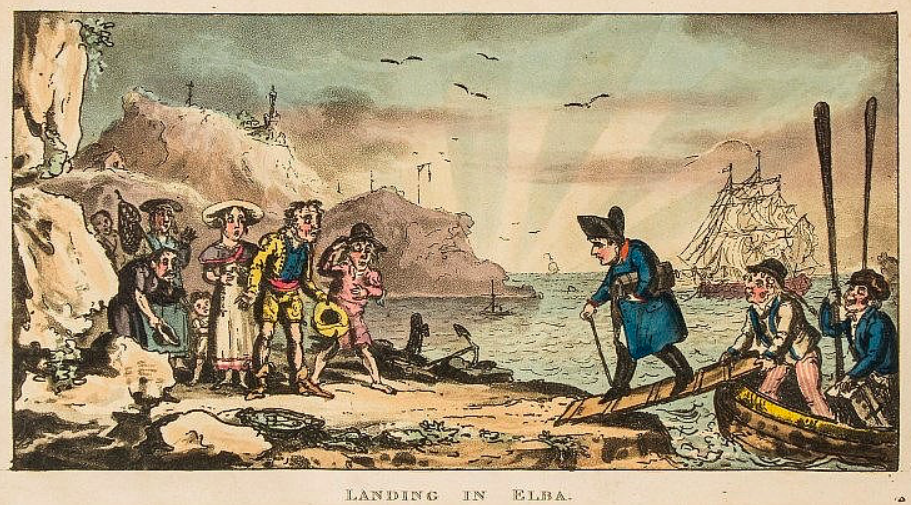

Link to blogpost in the blog “pastnow History, Arts and Stuff” and the picture of Napoleon.

When the emperor Napoleon was exiled on the island of Elba after his defeat in 1814, the island had 12,000 inhabitants. On his second day, the new king went for an inspection ride on this island, which is 224 km2 in size. He learned that his kingdom was much poorer than he had expected, and that the capital Portoferraio was a fly-buzzing stinking village with narrow alleys where garbage was thrown out into the streets.

With his usual energy and organizational ability, he turned the island upside down. He planted potatoes, lettuce and cauliflower to make Elba self-sufficient in vegetables, chestnut trees to prevent erosion, olive trees and vineyards. He enacted laws, organized garbage collection, arranged street lighting, improved schools and hospitals, and built facilities for trade and shipping. He “conquered” the neighboring island of Pianosa, dealt with the stray dogs, public hygiene and the construction of new roads. The large quantity of goods and supplies for the court and military personnel significantly increased trade and Portoferraio in particular benefitted from this.

For the first time in centuries, the Island of Elba was united under one flag (the only time, in fact, that it was united: today it is still divided into seven municipalities). Napoleon put Elba on the map and made it a more habitable island, addressing indicators 3, 8, 11, 23, 24, 27. 28, 34, 36, 38, 44, 46 and 47. He improved both the identity and the image of the island. Not bad for a ten-months stay.

Today, Elba is still known for Napoleon’s stay on the island and his actions to turn the island more habitable, a story often told.

The island is divided into seven municipalities: Portoferraio (which is also the island’s principal town), Campo nell’Elba, Capoliveri, Marciana, Marciana Marina, Porto Azzurro, and Rio. We refer to the island as a whole.

| Printed media last year | Number of printed articles | 2,5 | |

| Hits on the internet | 24 million hits | 4 | |

| Population growth 2001-2020 |

Portoferraio | +3% | |

| Rio | +6% | 4 | |

| Porto Azzurro | +15% | ||

| Capoliveri | +26% | ||

| Campo nell’Elba | +12% | ||

| Marciana | -2% | ||

| Marciana Marina | +0,5% | ||

| Published research | Number of scientific papers | 3 | |

| Active diaspora | Unknown | ||

| Survey | Not made | ||

Elba scores a 3, thanks to Napoleon and the island’s growing population.

References

The Habitability Handbook – An assessment tool for viable island communities by the Archipelago Institute at Åbo Akademi University is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.