Islands are, in many aspects, different and peculiar societies. Among the more than two thousand inhabited islands in Europe, including its overseas regions, 3 are countries, 39 are regions, states or provinces, 205 are municipalities, and 1,915 are local communities.

Some 1,453 islands are coastal, located less than 12 nautical miles from the mainland coast; 301 are in the high seas, located beyond a country’s territorial sea, more than 12 nautical miles from the coast; 397 are tied to the European mainland by bridges or tunnels.

With all respect for islands that are regions, states or countries, located in other continents, or have bridges or tunnels to the mainland – the 45 indicators of this tool won’t fit. They lack the geophysical and economic challenges that unbridged islands face, and they have jurisdictional autonomy to manage their own affairs.

| Political dimension | |||||

| Local community – no jurisdiction |

Municipality | Region, state or province | Country | ||

| Geographical dimension | Overseas | 54 | 3 | 10 | 1 |

| High seas | 148 | 87 | 18 | 2 | |

| Coastal | 1 339 | 83 | 5 | 0 | |

| Bridged | 354 | 29 | 4 | 0 | |

The Oxford English Dictionary defines subsidiarity as “the principle that a central authority should have a subsidiary function, performing only those tasks which cannot be performed at a more local level”. The principle of subsidiarity is to guarantee a degree of independence for a lower authority vis-a-vis a higher body or a local authority vis-a-vis the central government.

The primary subjects of the habitability analysis are the 1,487 local communities and 170 municipalities located inside the European continent but not attached to it with a fixed link. These 1,657 islands cannot govern themselves and typically have a weak representation before their municipalities, shires or counties. Their constraints and challenges are seldom understood, and they are frequently regarded as a cost, not an asset.

This level of local governance is important to keep in mind when analysing indicators for public service: daycare, school, elderly care, healthcare, solid waste, taxes and subsidies.

As stated in the introduction to this Handbook, you sometimes have to consider how you use, or if you can use, the different indicators for your island. If the island is very small or situated in an archipelago, the service in question might be lacking on that very island – but a well functioning service might be available on the neighbouring island instead. Then, it is up to the islanders to decide if, for example, “your school” is the school on the neighbouring island. If the logistics are functioning well and the islanders are happy with this solution, this is absolutely not a problem, and you should do the analysis accordingly. If this, however, is seen as a problem, you might want to tackle the indicator differently. The main thing is to describe the choices you make and why.

References

Indicators in the Public Services area:

- (32) Local governance

- (33) Daycare

- (34) School

- (35) Elderly care

- (36) Health care

- (37) Solid waste

- (38) Tax and subsidies

Indicator 32: Local governance

a Rationale

The small island communities for which the habitability concept is intended can either be part of a land-based municipality, be an independent municipality, or make up several municipalities. The first case is common in northern Europe, the second is common among Atlantic islands, and the third in the Mediterranean region.

The local administration can be municipal, an island council or committee, another collaborative body or nothing at all. It is governed by a complex collection of European, national, regional and municipal laws, regulations, ordinances, instructions, initiatives, programs and projects that can apply to everything from agricultural subsidies, schools, renewable energy, rents, municipal mergers, child benefits, ferry itineraries and other things that affect habitability. The administration can be placed out on the island or on the mainland.

Responsibility for islands’ development and sustainability is shared, fragmented and difficult to understand. Who rules, who has power and money, whose values govern planning and budgets?

Using indicator 32, we measure the degree of autonomy with which the island is managed. We try to understand the extent to which the islanders can influence the public administration of their habitability.

Cooperation is a way of finding financial resources to develop the island community, outside the ordinary resources of the local administration. Islands can cooperate in different ways, with different strategies. You can use several strategies – if you have the energy and skills. Islands can (1) enter into a bilateral alliance with a strong partner that can provide resources, (2) enter into a broader, multilateral partnership with several other similar islands, or (3) work to have laws and regulations that give the island advantages and protection in regional, national and EU contexts.

1 Bilateral relations

Collaborating with a large partner can be smart but requires the smaller party to succeed in making the larger party aware of its value. Helgoland (indicator 23) takes help from E.ON, RWE and WindMW to develop energy and business, Lidö in the Stockholm archipelago cooperates with the oil company Neste, Ven (indicator 26) made its parent municipality Landskrona aware of how much the islanders of Ven consume on the mainland.

2 Multilateral relations

Intranational networks

Many islands form cooperatives, networks and associations within their own country, to be stronger together. “Four brave men who do not know each other will not dare to attack a lion. Four less brave, but knowing each other well, sure of their reliability and consequently of mutual aid, will attack resolutely. That is the science of the organisation of armies in a nutshell.” (Ardant du Picq, Études sur le combat, 1880).

In France, Les îles du Ponant is the representative body of fifteen inhabited offshore islands of the Atlantic and Channel Sea coast. 576 Swedish islands formed Skärgårdarnas Riksförbund in 1982. In Denmark, Sammenslutningen af Danske Småøer, founded in 1974, represents 27 small islands that are not municipalities. FÖSS is the association for Finland’s 431 small, inhabited islands. The Scottish islands fall into six different local authority areas – Shetland, Orkney, Western Isles, Argyll & Bute and North Ayrshire, but are united in the Scottish Islands Federation. 33 Irish islands are represented by Comhdháil na nOileán, registered as a co-operative society in 1994. The Association of Estonian Islands promotes development and sustainable populations on 16 islands. 29 Greek islands have formed the Hellenic Small Islands Federation. 29 inhabited Italian small islands are represented in the Associazione Nazionale Comuni Isole Minori. In Croatia, Pokret Otoka is an association helping and promoting the 48 inhabited Croatian islands and life on them, advocating action towards sustainable development.

International networks

There are also many international networks facilitating the circulation of information among its members, allowing comparison of how different countries cope with issues, share knowledge, and influence EU institutions.

The European Small Islands Federation (ESIN) is the voice of 359,357 islanders on 1,640 small islands. CPMR has an Islands Commission covering nineteen European regional island authorities located in the Mediterranean and Baltic Seas and the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans. The Network of the Insular Chambers of Commerce and Industry of the European Union (INSULEUR) aims to promote the economic and social development of EU islands.

EU initiatives

Through a number of initiatives and programs, mainly to address high energy consumption, the EU invites its islands to develop a long-term framework for energy transition. Initiative and program examples include; the Clean Energy for EU Islands Initiative; NESOI, New Energy Solutions Optimized for Islands, which provides small grants and technical assistance; Smart Islands Initiative, a bottom-up effort; the Observatory on Tourism for Islands Economy (OTIE), which offers data and research.

There are also global networks such as Italian-based Greening the Islands (GTI), which focuses on energy innovations, and the French-based Small Islands Organisation (SMILO), which promotes and finances community-led solutions that enhance small island sustainability.

For an island, there is thus no lack of possible support. It’s a question of choosing the right strategy and a fitting partnership. You don’t have to go all the way like Cinderella when she slipped out of her family prison to enter a totally new relationship; you can have both.

3 Laws

Some countries have an island or archipelago law describing the rights and obligations of islanders, notably to force municipalities to create reasonable socio-economic conditions for people on the islands. Such is the case in Croatia, which has an Islands Act from 1999, revised in 2018. Finland has a law promoting archipelago development from 1981, which will be revised shortly.

Other islands have secured a position of their own, often as “tax-havens” – a jurisdiction with very low “effective” taxation rates for foreign investors. On a general level, the Netherlands and Ireland are considered as tax-havens. On an island scale, the Channel Islands and the Åland Islands have tax exemptions regarding alcohol and tobacco, which is also the case on the tiny island Helgoland (indicator 23). Bø (indicator 38) altered its wealth tax level in opposition to its shire and the whole nation.

b Definition

Level of self-governance attained through bilateral and multilateral partnerships and jurisdiction.

c Computation

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Local community without decision-making power | Local community with limited decision power | Municipality | Region, county or state |

| No bilateral partnerships at all | One bilateral but not very active partnership | One bilateral active partnership, to some use | One or several active and very useful bilateral partnership(s) |

| No multilateral partnerships at all | One multilateral but not very active partnership | One multilateral active partnership, to some use | One or several active and very useful multilateral partnership(s) |

| No island law | Islands are mentioned in regular laws | Island law but not very useful in practice | Powerful island law |

| No exemptions | One but not very useful exemption from national law | One useful exemption from national law | Ample exemptions from national law |

Count the average value for your island.

d Example

Susak is a small island located in northern Croatia, southeast of the Istria peninsula. It covers a surface of 375 hectares. Compared to the neighbouring islands of Lošinj, Unije, Vele Srakane, Male Srakane and Ilovik, Susak looks unusual. The many flat terraces used for cultivating vine give the island a “stepped” appearance. A lighthouse rests on the highest part of the island, with its lightroom 100 metres above sea level. This light is one of the main landfall lights on this part of the Adriatic coast.

In the past, Susak’s inhabitants mostly made their living from farming, fishing, and winemaking. The economy flourished until the middle of the 20th century; a fish cannery was operating on the island until the 1940s, and a cooperative wine cellar was running from 1936 to 1969, processing 1,400 tonnes of grapes each year. The island even had an indigenous red grape variety called Sansigot. Almost a third of the entire island’s surface was planted with Sansigot, which flourished on the sandy soil.

After the end of World War II, Susak became part of Yugoslavia. The Communist regime launched a nationalisation process and agricultural reform, and the majority of the population decided to leave the island for either political or economic reasons or both. In 1948, the island had 1629 inhabitants. During the following 23 years, the number of inhabitants dropped by more than 1300 persons. From 1971, the population has continued to decrease to the current number of around 150 residents.

Most fled via Italy to Hoboken, New Jersey; others have moved to France, Canada, Argentina, and Australia. Nowadays, the largest number of families originating from Susak reside in New Jersey and the wider New York City area, and it’s estimated that the Susak diaspora based in the US currently counts between 2,500 and 4,000 people. They are crucial supporters of Susak today and an example of how population growth and development can be totally governed by external forces, as thoroughly described in the study “Lost in transition – the island of Susak”.

The local community of Susak is weak (1) but has a very strong external partnership (4), a not very active national island partnership (2), and a functioning island law (4) but no exemptions (1). This gives Susak an average value of 2,4 = 2.

References

- Demark, N. 11 January 2018. Diaspora Roots: Susak Island. Total Croatia News.

- Finlex, 26.6.1981/494. Lag om främjande av skärgårdens utveckling. (Finnish Archipelago Law).

- Islands Act of Croatia, from 1999, revised in 2018 (PDF).

- Mesarić Žabčić, R. 2016. Emigration from the island of Susak to the United States of America. Croatian Studies Review 12.

- Orovic, J. 2018. Croatian Islands Hope New Law Fixes Old Problems. Total Croatia news.

- Rudan, I, Stevanović, R & Vitart, V. 2004. Lost in transition – The island of Susak (1951-2001). Collegium Antropologicum 28(1):403-21.

Indicator 33: Daycare

a Rationale

Kindergarten and daycare are important requisites for a functioning working life for both children and parents.

b Definition

A balanced assessment of the staff’s training and adequacy, vacant daycare places, resources, activities, and suitable opening hours.

c Computation

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Personnel and their competence | Continuous lack | Sometimes lack of personnel or lack of personnel who have the right training | There is personnel, but not all have the right competence | All personnel at hand with the right competence |

| Age distribution | Children are missing in five age groups | Children are missing in three or four age groups | Children are missing in one or two age groups | There are children in all age groups |

| Available daycare | Lack of vacancies | Some lack of vacancies | Just the places needed | No lack of available daycare |

| Resources for activities | Lack of resources | Some lack of resources | Just the resources needed | Lots of resources |

| Activities concerning sustainability and island identity | Not included | A few times per semester | Once a week | Daily |

| Daycare time | Does not match at all | Some needs cannot be met | Regular needs can be met | All needs can be met |

| Sum A + B + C + D + E + F / 6 = | ||||

d Example

The island of Houtskär, with about 500 all-year residents, is situated to the far west in the Southwest of Finland. To reach the mainland, you use three different ferries. The connection between Korpo and Houtskär is the longest crossing for the yellow road ferries carrying cars in Finland: 9.5 kilometres. Houtskär ceased to be a municipality of its own in 2009 and instead became part of the city of Pargas. Houtskär offers a good basic service that is complemented by private companies. The activities of different island associations contribute greatly to the well-being of the inhabitants.

The kindergarten in Houtskär has places for 21 children: from 1-year-old babies to 6-year-old children, in preschool, which in Finland is the last year before school starts at the age of seven. In 2022, 19 children are recorded as being in daycare on the island.

The kindergarten has become a pioneer in sustainability in recent years. The personnel strive to include the local environment and everything that the archipelago nature offers in their activities for children. They freely move around with two electric bicycles that seat five children each.

Local food is used in the kitchen, and the kindergarten has its own garden where vegetables are grown. It tries to minimise food waste and uses the bokashi method for composting. The kindergarten is located in the Archipelago Sea Biosphere Reserve. It utilises the biosphere reserve’s program, “Superheroes of the archipelago”, where children gather knowledge about nature, sustainable development, island identity and their own roots in the archipelago.

The computation for the kindergarten in Houtskär would be:

| Personnel | 3 |

| Age distribution | 4 |

| Available daycare | 4 |

| Resources | 4 |

| Activities | 4 |

| Daycare time | 4 |

| 3 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 / 6 = 3,8. The value for Houtskär is 4. | |

Indicator 34: School

a Rationale

A school on a small island is the central point on which the society balances. The school is vital for families with school-age children – both its existence and its qualities. A well-run school is important for children and the well-being of the parents and the staff.

b Definition

The staff’s adequacy and competence, access to resources for desired activities and extra

support, the children’s age distribution, and whether children go on to higher education after upper secondary school.

c Computation

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Enough staff with adequate competence | Continuous lack | Sometimes lack of personnel or lack of personnel who have the right training | There is personnel, but not all have the right competence | All personnel at hand with the right competence |

| Resources for activities | Lack of resources | Some lack of resources | Just the resources needed | Lots of resources |

| Age distribution | Children are missing in five or more classes | Children are missing in three or four classes | Children are missing in one or two classes | There are children in all age classes |

| Resources for activities | Lack of resources | Some lack of resources | Just the resources needed | Lots of resources |

| Activities concerning sustainability and island identity | Not included | A few times per semester | Once a week | On a daily basis |

| Continued education after elementary school | Less than 50% | 51-70% | 71-85% | Almost all pupils continue their education after elementary school |

| Sum | ||||

d Example

The French mainland’s furthest outpost in the west is Ouessant (called Ushant in English). The island is a rocky landmass with a total area of 15 km2 in the Iroise Sea on the French side of the English Channel. These dangerous waters are amongst the most troublesome in the world, with 10-knot tidal streams and numerous sharp reefs both over and under the water surface. To protect ships and sailors, no less than five lighthouses beacons are surrounding the island, including one of the world’s strongest, Phare du Créac’h. It can be seen from 60 kilometres away.

In 2019, the population was 833, reduced by half since 1968. In summer, the population is at least 2,000. The number of second homes was 360 in 1990 and is now reaching 500. The island has about 150,000 one-day visitors per year, giving a locals-to-tourist ratio of 1:170.

Administratively, Ouessant is a municipality of the Finistère in the Brittany Region.

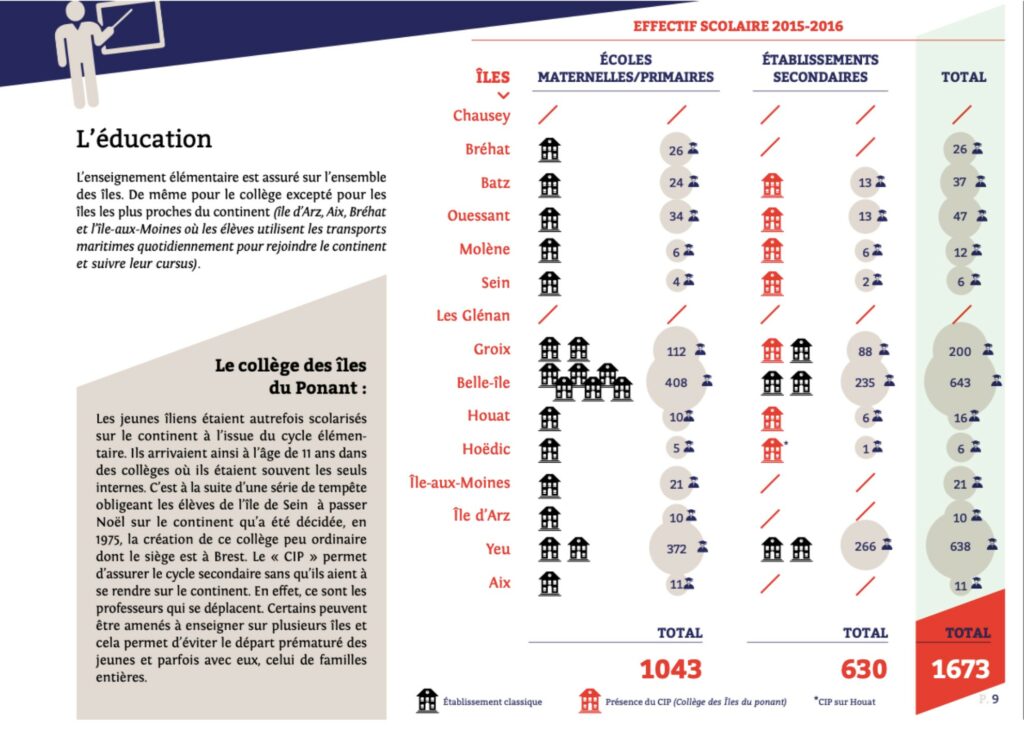

In the previous school system, children from the age of 11 were sent to schools on the mainland where they were often the only ones living in boarding schools. When a series of storms in the winter of 1975 forced children from the neighboring island of Île de Sein to remain on the mainland over Christmas, parents and islanders had enough. Instead of moving the children, it was decided to move the teachers. In 1976, Ouessant together with the islands of Batz, Molène, Sein, Groix, Houat and Hoëdic created the Collège des Îles du Ponant network school with a capacity for about 100 students. The school is a combination of 26 traveling teachers with good working conditions and strong technical support, and distance learning.

In 2021, close to 100 students attend this school. Ouessant has 40 students at primary school level and 14 students at secondary school level. The study results are good.

On a higher level of education, there is a triple helix cooperation between l’Université de Brest, l’Association des îles du Ponant and the Region of Brittany. It was initiated by the university and the association in 2016, followed by a feasibility pre-study the next year, whereafter the Region of Brittany joined the cooperation. Three islands stood out as primary objects in the following years: Sein, Molène and Ouessant. A communication program started when 20 teachers/researchers joined the initiative, and a Master’s program was organised, which in 2019 had 46 students writing their theses on subjects from these islands. Since then, several programs and theses have been applied mainly on Ushant, two of these are still active in 2022.

The cooperation has successfully pinpointed what is needed to keep these 15 islands habitable. At present, there are 15 ongoing research programmes, among them indicators of well-functioning social services such as daycare, healthcare, elderly care and the unusual school system, which moves teachers instead of pupils.

For Ouessant, the computation would be:

| Staff: | 3 |

| Resources: | 3 |

| Age distribution: | 4 |

| Activities: | 4 |

| Continued education: | 4 |

| 3 + 3 + 4 + 4 + 4 = 3,6, giving an indicator value of 4, which this school system well deserves. | |

References

- Id-îles, Le Magazine des Initiatives et du Développement dans les îles du Ponant.

- Les îles du Ponant, L’esentiel 2018 (PDF).

Indicator 35: Elderly care

a Rationale

A habitable island can take care of its elderly population and avoid sending them to institutions on the mainland. Older populations being away from their relatives and homeland and among unknown caregivers can be at great risk for loneliness and depression.

An elderly person’s home is also an important workplace on a small island.

b Definition

Distance to and availability of vacant care places, the staff situation and the quality of care.

c Computation

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Distance | No municipal elderly care on the island, distant solutions | No municipal elderly care on the island, but there is care quite close on the mainland | Elderly family care with strong support from the municipality | Most elderly people, unless with complicated health, dementia, or palliative care, are taken care of on the island |

| Availability | Very long waiting time | Long waiting time | Enough support, short waiting time | Enough places, short waiting time |

| Competence | No local competence | Personnel who have the right competence on the mainland | Most of the necessary personnel with the right competence | All the necessary personnel with the right competence |

| Quality | There are always complaints from caretakers and families |

Many complaints from caretakers and families |

Some complaints |

No complaints |

| Sum |

d Example

Finland has more than 500 islands with full-time settlements and almost 20,000 islands with part-time settlements without a fixed road connection. Including Åland, the country has about 100,000 resident islanders. Many of the islands along the coast of Finland and inland have a declining population, weak attractiveness for immigration, and strong seasonal variation due to intense tourism pressure. Consequently, many municipalities face challenges in establishing a basis for service provision, including healthcare, schools, and social care. Finland also has an elderly population profile, increasing the demand for healthcare and care services.

The island of Bergö on the shores of the Bothnian Bay is approximately 3.15 km2 in size, with a population of 470. Once an independent municipality until 1973, Bergö is now a part of Malax. The ferry from the mainland port, Bredskär, takes 10 minutes with almost 50 round trips a day. Islanders can use a bus to commute to Vaasa town – once a day. Sixty people are working on the island, 22 of which are whitefish fishermen, landing some 250 tonnes a year. There is a grocery store, a library, hairdresser, flower and gift shops, and a café on Bergö. Municipal water and wastewater treatment services are available for around two-thirds of households, and energy is brought to the island with a cable from the mainland.

The island council, Bergö öråd, was founded in 2002 with the idea of building a new common service house on the island. At that time, when elderly people could no longer stay by themselves, and there were no possibilities to take care of them in the family, the only alternative was to move to the mainland. For relatives, a visit meant a three-hour journey by car or taking a bus at eight o’clock in the morning, returning at four o’clock in the afternoon. In addition to this, the cost of the service was high, and possible workplaces on the island were lost.

The islanders accomplished a combined solution incorporating a primary school, a public library, a service housing for older people, a health station and mobile care facilities. This was a locally-led initiative by the island council and a related working group, which persistently advocated for local development, organising joint activities and seeking state and municipal funding to make an “under-one-roof” solution possible: a new service building for the whole island.

Evaluation of the elderly care on Bergö:

| Distance | 4 |

| Availability | 3 |

| Competence | 4 |

| Quality | 4 |

| 4 + 3 + 4 + 4 = 15/4 = 3,8. The value for Bergö is 4. | |

Time has shown that the waiting time, i.e. availability, is the most problematic factor on Bergö. The need for caretaking places was underestimated while planning for the centre; 10 places are simply too few. As of spring 2022, 3-4 elderly people from Bergö are taken care of on the mainland.

The service house, which came to expand into a multi-functional service centre (or ‘service bundle’), combines elderly care with healthcare, welfare/social care, education, and cultural services. Of real importance is the link between younger and older islanders. A combined initiative now enables older people to stay on the island when they require special care and young children to receive an education close to home, creating workplaces on the island. Bergö illustrates a process in which locally-led service provision has been successfully designed through a combination of hard work, community spirit and collaboration, and long-term dialogue with the local municipality and state support.

References

- Cedergren, E, Huynh, D, Kull, M, Moodie, J, Sigurjónsdóttir, H, Wøien Meijer, M. 2021.

- Bergö: Locally initiated service housing became a multi-functional service centre. In:

Public service delivery in the Nordic Region: an exercise in collaborative governance. Nordregio Report 2021:4. - Prost, P. 2019. Bergö vägvisare för nya servicelösningar i skärgården. Tidskriften Skärgård 4/2019.

Indicator 36: Healthcare

a Rationale

Public healthcare should prevent diseases, promote health and prolong life. It is a complex indicator as the “public” could be a handful of people, a city or an entire nation. It is part of a country’s overall health system and is implemented through the surveillance of health indicators.

Safe and good healthcare is an important ingredient in making an island habitable and, of course, an important tool for maintaining good health among the islanders.

b Definition

An overall assessment of the health care services offered for the islanders and the availability of health-promoting activities.

c Computation

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Healthcare | |||||

| a | Access | Unaccessible, hard to book a time | Not so accessible and sometimes hard to book a time |

Quite accessible, easy to book a time |

Very accessible, very easy to book a time |

| b | Care | Lots of deficiency |

Some deficiency |

Good | Very good |

| Doctor | |||||

| c | Access | Unaccessible, hard to book a time | Not so accessible and sometimes hard to book a time |

Quite accessible, easy to book a time |

Very accessible, very easy to book a time |

| d | Care | Lots of deficiency |

Some deficiency |

Good | Very good |

| Dentist | |||||

| e | Access | Unaccessible, hard to book a time | Not so accessible and sometimes hard to book a time |

Quite accessible, easy to book a time |

Very accessible, very easy to book a time |

| f | Care | Lots of deficiency |

Some deficiency |

Good | Very good |

| Health promotion | |||||

| g | Activities | Lots of deficiency |

Some deficiency |

Good | Very good |

| Sum of obtained values, divided by 7: (a+b+c+d+e+f-g)/7 | |||||

d Example

Situated in Bantry Bay is the Irish island Bere. It is the second-largest Irish island, discounting islands connected by causeways or bridges. It has a population of 160 people (a sharp decline from 216 people in 2011 and its peak back in 1926 with 1,182 all-year inhabitants). About a third are elderly, and a number have underlying health issues.

Bere matches its dwindling population with a phenomenal community spirit, which binds the island community together. Many visitors are attracted to the island because of all the different events arranged by the islanders – the list of activities would put many large towns to shame. The events include sending a lorry to Ukraine on St Patrick’s Day (March 17, 2022), preparing a religious retreat at Easter, an islands’ festival in June, a children’s summer camp in July, a heritage week in August, and an all-island football tournament in September. With hotels, B&Bs, Airbnbs, bars, cafes, restaurants, and its Bakehouse Cafe with its sizzling garlic prawns, the overriding impression of Bere Island is of a thriving island community.

The Bere Island Projects Group (BIPG) is a non-profit organisation with two employees, John Walsh and Laura Power. John, who is also the chairman of the European Small Islands Federation, says BIPG deals with every issue from the cradle to the grave, working to sustain the island population through the creation of employment, promoting community initiatives and supporting local businesses.

In 2018, the general nurse working on Bere was taken from the island to the mainland on various days to cover planned and unplanned leaves by colleagues. This left many on the island without a service – a very worrying time for the residents who feared that this was the beginning of a withdrawal of the service. Then came COVID. In March 2020, Bere Island asked people not to visit as part of an effort to protect the elderly living there. BIPG made the appeal after discussions with the local ferry company and health professionals, and they were trying to limit the number of trips islanders have to make to the mainland. The island also had an active age scheme with a list of people willing to do messages and jobs for the elderly and a strong, active retirement group, which would also be mustered to help.

Today, Bere has a nurse on the island, and the local project group does some health promotion work for the islanders. The doctor and the dentist are on the mainland, in the town of Castletownbere, where the ferry lands. The town has two doctors and a dentist. Sometimes, you have to travel to the city of Cork, two hours away, for a dentist and hospital appointments. Coming out of COVID in the spring of 2022, the coordinator of BIPG assesses the healthcare situation as follows:

| Healthcare | a Access | 3 |

| b Care | 4 | |

| Doctor | c Access | 3 |

| d Care | 4 | |

| Dentist | e Access | 2 |

| f Care | 4 | |

| Health promotion | g Activities | 3 |

| Total | 23 | |

| Sum of obtained values, divided by 7 (a+b+c+d+e+f-g)/7 | 3.3 | |

The indicator value for Bere is 3.

Addition

In 1984, sixteen islands founded Comhdháil na nOileán – the Irish Islands Federation. At that time, there were serious shortcomings regarding access to the islands, healthcare, and other essential services. Currently, there are 33 member islands with populations from just one person to 824 and a total combined population of just under 2,900.

The Irish Government started working on an Islands Policy Consultation Paper in November 2019. Regarding healthcare, the consultation states that “the challenge is to support individuals living on the islands to be as healthy and resilient as possible while providing appropriate and accessible services that reduce the risk of hospital admissions and facilitate people to remain living on the islands. This is not a straightforward task given that the islands, by their very nature, are remote and isolated places, while the availability of services can vary and is often at the mercy of poor weather conditions and limited transport availability. It can also be difficult to attract and retain healthcare professionals to serve island communities.”

Regarding healthcare, Comhdháil na nOileán has demanded that the additional time and costs involved in visiting patients on the islands should be taken into account when allocating workloads and budgets for Public Health nurses; also, the cost of accommodating relief nurses on the islands should be reimbursed, and island women should be offered greater choice in maternity care, including visits on the island from a midwife.

References

- European Small Islands Federation.

- Islands Policy Consultation Paper. 2019. Government of Ireland (PDF).

- O’Riordan, S. 2020. Bere Island self-isolates as residents ask for no visitors. Irish Examiner.

- Southern Star Team. 2018. Bere Island nurse being shared with mainland to cover unplanned leave. The Southern Star.

Indicator 37: Solid waste

a Rationale

Waste management in small island communities is complicated by their geographical setting and an often tourism-dominated economy. They frequently rely on imported products and choose not to control the “waste-to-be” being brought to the island.

People in the EU generate roughly 505 kg of municipal waste per person per year, of which 48% is recycled (2020). Some countries generate less and some more, ranging from as low as Romania’s 280 kg to Denmark hitting 844 kg per person. Waste from tourists is produced at almost twice the rate of locals. Including waste from the construction sector, mining, quarrying and manufacturing, we generate 5.2 tonnes of waste, of which 39% were landfilled and 38% were recycled.

Due to financial resources and limited land availability for disposal, the quantity of waste is often beyond what the island can handle. This situation is further complicated as islands often have difficulties finding markets for re-sale recyclables on the mainland. As a result, solid waste on small islands has often been managed through open dumping on land, in water, and open-pit burning, with limited recycling. The generation of waste makes the island less habitable through widespread environmental, social, and economic impacts. Preventing waste is always the first option, and sending waste to landfills (on the island or the mainland) is the last one.

b Definition

The percentage of waste being recycled, excluding construction waste.

c Computation

| Total tonnes per year | Amount recycled | |

| Combustible waste | ||

| Carton | ||

| Newspaper | ||

| Plastics | ||

| Metal scrap | ||

| Glass | ||

| Inert waste | ||

| Dangerous waste | ||

| Sum |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 to 25% is being recycled | 25 to 50% is being recycled | 50 to 75% is being recycled | Over 75% is being recycled |

d Example

Porquerolles, an island on the French Mediterranean coast, has a permanent population of 350 inhabitants throughout the year. For many centuries, Porquerolles had a mere military function, and a village was built in the 19th century to accommodate the military families. For almost 60 years, beginning from 1912, the island was private property. In 1971, 80% of the island was sold to the French Government, and it became a National Park in 1985 – one of ten car-free islands in France.

There is a challenge to reconcile tourism and protecting the island’s fragile environment. One of the beaches on Porquerolles – la plage de Notre Dame – was selected as the most beautiful beach in Europe in 2015. Every summer, one million tourists visit the island. The daily average is 6,000 visitors, sometimes as many as 9,000. Most of these are day-trippers, but there can also be some 1,500 boats, of which 500 stay overnight. In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic forced the French to take their holidays in France, causing an over-frequentation of tourist places. Porquerolles peaked on July 13, 2020, with more than 15,000 visitors, which, among other problems, caused a freshwater shortage.

The considerable number of visitors to the island generated much waste, as we humans always do. Before 2020, the waste collected amounted to 2,214 tons of cardboard/paper, 1,200 tons of glass, and 276 tons of plastic waste. The average French person generates 546 kg of waste per year, but the residents of Porquerolles only produce 191 kg each. But the one million visitors, as well as the hotels, restaurants, and private boats, add approximately 4,000 tonnes of solid waste.

The terrain on Porquerolles is not easy. While the roads are sealed in the village and the harbour, there are only dirt roads on the rest of the island. Furthermore, the space – especially in the village – is very constrained. This poses challenges for the collection of waste and storage of containers.

Garbage is collected every day from 5 to 10 am, beginning in the village, then on the beaches on the west side of the island, and then back to the village. The team also collects paper from the “savage toilets” – no wonder on an island with public toilets only on one of the beaches. In the evening, the team notes the volume and type of waste collected, including driftwood, and where it has been collected.

The transfer and transport of waste come after collection. While non-recyclables are shipped every day to the incinerator on the mainland, recyclables are first stored in containers in a transfer zone on the island until they are full. They are then transported by ferry to the mainland, which adds considerable costs.

There are four authorities on the island: the national park, the municipality of Hyères, the authority of the ports of Toulon, and IGESA, a French army institute that runs a vacation site for military personnel and their families. Each of these has its own waste policy and storage facilities; for example, in one part of the island, they demand you to separate your waste, and they do not in another part of the island. This makes it almost impossible to know how much waste is produced per fraction on Porquerolles, but we know that of the total amount of waste transported from the island, 30% was recycled, 8% composted, 42% incinerated and 20% landfilled.

This gives the island of Porquerolles a value of 2.

The islanders themselves are unsatisfied. There is too much garbage left on their beautiful beaches. On three days in January 2020, 55 volunteers assembled 1.6 m3 of waste along 3,000 meters of shore in 30 hours. The waste included: 650 litres of polystyrene, 642 bottle caps, 226 plastic bottles, 200 cotton swabs, 120 empty cartridges, 100 plastic cups, 62 lighters, 42 shoes/sandals, 41 metal cans, 35 ballons/balls, 22 diapers, 20 coffee filters, 12 syringes, six bait boxes, five pieces of clothing, two tires, two fishnets, one battery, and three litres of cigarette butts.

In early July 2021, a year after the invasion of July 13, 2020, the Municipality of Hyères, the Métropole Toulon-Provence-Méditerranée, the National Park of Port-Cros, the company in charge of the public transport service between the mainland and Porquerolles, and representatives of the 12 shipping companies, which also provide maritime shuttles, agreed to set a threshold for the flow of visitors at 6,000 per day.

“An island jewel for which the situation was no longer tenable”, said Jean-Pierre Giran, Mayor of Hyères, and continues: “We could have tripled the fare, but ultimately only the rich could have come. It is anti-democratic. With this gauge, we are taking an important step. It is an ethical and courageous act.”

References

- European Best Destinations. The best beaches in France.

- Eurostat: Municipal waste statistics.

- Reicehencker, A. 2016. The Shaping factors of waste separation on the island of Porquerolles. University of Wageningen.

- Marquès, C. 2021. La fréquentation touristique régulée cet été à Porquerolles. France Bleu Provence.

Indicator 38: Tax and subsidies

a Rationale

Taxes affecting island life are personal income tax, property tax, corporate tax, mandatory social insurance contribution, VAT, road tax and an energy tax. Subsidies can lower the effects of some of these taxes or insularity in general.

The relative importance of taxes and subsidies varies greatly across island nations. Focusing on a single instrument could be misleading. Personal income taxes often have a progressive structure and include different levels on all sources of earned income, wages, pensions and social benefits, for example, unemployment benefits. Taxes paid on income from capital are usually characterised by a more proportional scale.

Personal and income taxes represent less than 10% of GDP in France and Spain and almost 15% in Finland, to name three outstanding island nations in Europe. In all countries, mandatory social insurance contributions are levied on labour income from employees, although with a lower rate than on work, representing 10% of GDP in France, 5% of GDP in Finland and 4% in Spain. Wealth taxes exist in many forms in almost all countries, ranging from 1% in Finland to 3.5% in France.

VAT is levied at each stage of the supply chain, where value is added from initial production to the point of sale. VAT raises government revenues without punishing the wealthy. It is said to be an alternative to income tax – which is not necessarily true because many countries have both an income tax and a VAT.

In the previous habitability process, we have seen many examples of island overcosts and financial challenges such as in indicators 5 (skewed population dynamics), 6 (long distances), 7 (accessibility), 24 (viability of the business ecosystem), 27 (spending leakage), 29 (high cost of living) and 30 (affordable housing). The question is: are taxes and subsidies compensating islands for these challenges?

b Definition

The overall impact of taxes and subsidies on island life, compared to the nearest mainland town, municipality or region.

c Computation

| Issued by | Compared to mainland | |||||||

| Municipality | Region | State | EU | High | Low | Fair | Unfair | |

| TAXES | ||||||||

| Personal income tax | ||||||||

| Property tax | ||||||||

| Corporate tax | ||||||||

| Mandatory social insurance tax | ||||||||

| VAT | ||||||||

| Tax paid on income from capital | ||||||||

| Road tax | ||||||||

| Energy tax | ||||||||

| Other | ||||||||

| SUBSIDIES | ||||||||

| On ferry charge, persons and cars | ||||||||

| On ferry transport of goods | ||||||||

| On farming | ||||||||

| On fishing | ||||||||

| For business start-ups | ||||||||

| Tax exemption for example on alcohol & tobacco | ||||||||

| Other | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Taxes are unfair | Some taxes are unfair | Taxes are quite fair | Taxes are fair |

| No subsidies | Few subsidies | There are subsidies to a certain extent | Compensating subsidies |

d Examples

The most northern Norwegian shires are Nordland, Troms, Finnmark, and Svalbard, far up in the Arctic region. Here, schools, bathhouses, fire brigades, police stations and other municipal functions are maintained where only a few thousand people live. This is due to a whole set of subsidies: Mandatory social insurance tax is lower the further away you are from the big cities; Student loans can be depreciated for those who move to the countryside; Personal income tax, which is taxed at a flat rate of 23% in Norway, is lower in the northern shires: only 19.5%.

Langøya in Nordland, north of Lofoten, is Norways’ third island in size, 850 km2. It is divided into four municipalities: Bø, Øksnes, Sortdal and Hadsel. European Route 10 leads from the mainland to Hinnøya over the 1,000-metre Hadsel bridge to Langøya. Furthest to the east is Bø municipality, with 2,565 all-year residents, a steady reduction since the 1950’s when over 6,000 people were living here.

In addition to income tax and social security payments, Norway levies a 0.85% wealth tax on residents’ global assets above 1.5 million Norwegian crowns (154,000 euros). Of the wealth tax taken, 0.15% goes to the state, with the remaining 0.7% going to the municipality in which the individual lives.

Bø decided that from January 2021, it will charge just 0.2% wealth tax, meaning a drop from 0.85% to 0.35% for its residents. Bø’s conservative mayor Sture Pedersen hoped the tax cut would make some of the country’s richest move to Bø and lead to an overall income boost and new economic opportunities for the municipality. “Public authorities abandoned us years ago,” said Pedersen. “We do this to attract capital to our municipality. We need that to survive and to create jobs.”

Indeed, retired cross-country skier and cultural icon Bjørn Daehlie moved to Bø among a group of wealthy Norwegians. But there is an equalisation rule in Norway, which was not taken into account when the decision was made. Bø does not receive the full amount of wealth tax from the newcomers immediately, and, of course, the existing residents also get a reduced wealth tax. The sums simply don’t add up for Bø.

It seems the tax reduction was ill-managed and planned, scoring a 1, while subsidies in this northern shire of Norway score a 4.

References

- David Nikel. 2020. Wealthy Norwegians Are Moving To This Remote Tax Haven. Forbes.

- Skatteetaten. Finnmarksfradraget.

- Nilsen Trygstad, A & Jæger Kristoffersen, K. 2020. Tar med seg 2,2 milliarder til Norges nye skatteparadis. NRK.

- Hansson. E. 2016. Därför går det så bra för norska landsbygden och så dåligt för den svenska. Natursidan.se.

The Habitability Handbook – An assessment tool for viable island communities by the Archipelago Institute at Åbo Akademi University is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.